Tom Palen,a broadcaster, pilot, writer, and our Guest Columnist! Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Back to Blog

Pilgrims11/21/2018 With Thanksgiving upon us, I have once again committed to not overindulge this year. But, I said that last year, and the year before, and the year before that...

There’s just so much food and everything is so good. Moist turkey, stuffed with made from scratch sage dressing; mashed potatoes with homemade gravy, sweet potatoes spiced just right with marshmallows on top, green bean casserole with the crispy onion topping, our daughter’s spicy corn, fresh cranberry relish, the soft, warm, homemade dinner rolls right out of the oven... Oh my, and we haven’t even gotten to the pies yet! I’ve tried limiting myself to one helping - no seconds, but that caused me to pile the plate way too high with food the first time. I’ve tried a smaller plate, but found it can easily be refilled again and again. I even tried holding my fork in my left hand, once. That was a disastrous mess! Drinking a full glass of water before eating only added to being too full. I don’t normally eat that much, so, why do I do so every Thanksgiving? Maybe it’s the setting. A big feast spread out over a beautifully decorated table, with a real tablecloth and a festive fall centerpiece. Family and friends come together to celebrate. The atmosphere is warm and inviting. The food is so good and I do like eating, still, I have never liked the feeling of being stuffed to the point of being miserable. This year is going to be different. Before dishing up, I am going to ask myself, “Just how bad do I want it?” Instead of focusing on all the food, I’ll make a conscious effort to seek the true meaning of Thanksgiving - reflecting upon where it all started. A few years ago, Melissa researched my ancestors, seeking to find where they had originally settled when coming to the “new world.” She found it! We drove to the east coast that fall and ended up in Taunton, Massachusetts. Taunton is a small town about 24 miles due west, inland from Plymouth, where the famous Plymouth Rock marks the landing site of the pilgrims arrival in 1620. From Taunton, we drove to Plymouth, where we visited Plymouth Rock. It was an open monument type structure with tall pillars and a roof overhead. Inside it wasn’t much at first glance; just a rock petitioned off by three walls. We viewed it at street level. The rock itself sat down in a concrete well on the sandy beach. Leaning on the black steel railing above, we looked below. The tide was out so the rock sat alone. The date, 1620, engraved in the rock, was weathered from years of waves splashing against it, wearing it down. I was trying to imagine myself being on that voyage. The ship must have been anchored in the bay and the pilgrims came to shore in rowboats, I suppose. There was no fancy dock, nor a welcoming committee - just a rock on an empty beach and woods before them. I felt a chill; an eerie feeling, knowing those people arrived with no place to go; no shelter of any kind. They had to make due with only that which nature offered, the few provisions they brought with them and their faith in God to provide a better future. It was humbling to say the least. Our next stop was to visit the Mayflower II; an exact replica of the original ship on which the pilgrims arrived. We were going to bypass the boat on this trip as it was a grey cloudy day. It was cold and spitting rain on and off. The east wind blowing in across the cold waters of Plymouth Bay seemed to penetrate right through my coat, chilling my bones! It wasn’t the best day for touring an open boat, but we were told the ship would be leaving at the end of this season; in just a few days. She would be taken to a shipyard where she was scheduled for a major restoration and wouldn’t return for three years. The ship would be back in time for the 400th anniversary in 2020. We decided to go check out the boat, which was a short walk from Plymouth Rock. Crossing the walkway onto the deck of the Mayflower II was like stepping into a time machine. There were plenty of staff members on board. Those who were dressed in normal clothes and wearing a name tag, could answer any questions you had. Others dressed in 1620’s clothing could answer questions, but they had to speak in the period. That was interesting. Keep in mind there was no such thing as political correctness in 1620. One just said what was on their mind. I overheard a shipmate telling a story to another guest. He was speaking about Irishmen, and not fondly. Being Irish on my mom’s side, I was a bit taken aback by his comments. When he was done talking with the other person, I queried the shipmate, “Excuse me. Why did you say the Irish were worthless?” He clarified, “I didn’t say they were worthless. I said they were no good. Not a one of them.” He warned me, “You’d best listen to what I say if you’re going to repeat me. No man is without worth, not even a bloody Irishman.” He continued, “The Irish are very strong men. Then can lift a heavy load and do the work of two or three men. But that’s where he comes to limits. They’re as useful as an ox. Oxen are hard workers too, but you certainly wouldn’t take an ox into your cottage. Irishmen belong in the barn with the livestock.” Curious, I asked, “Why do you say they’re no good?” I listened as he continued, “They’re no good because they’re mean and they like to fight. And do you know why they’re mean?” He answered before I had a chance, “It’s because of their bloody Irish tempers. And do you know where they get those tempers? It’s from their fiery red hair. I suppose I would be mean too, ifin’s I had red hair.” It was humored listening to him. “Do you know where they get that red hair? I’ll tell you. It’s from eating their meat undercooked! Raw meat will turn your hair red, you know.” “I take it you don’t like the Irish.” I said to him. “What’s to like about them?” He replied, “I go to the pub to have a pint with my pals; to tell some tales and have some laughs. When the Irish come, they aren’t satisfied with a pint - they gotta be drinkin’ that Irish whiskey of theirs, and the next thing ya know, they want to fight. Well after a couple pints my pals and I are ready to give those Irishmen a poke right back in their nose!” He wasn’t done yet. “Once we’ve put them down and tossed them out onto the cobblestone, those Irishmen go to the brothels, but the ladies will have nothing to do with such drunkards, so the men go home to their wives. Their women don’t want anything to do with them in such a drunken stupor. The Irishmen don’t have sense enough to leave an angry woman alone, and the next thing you know, she’s with child. Well when you have an angry husband and an angry wife, it only stands to reason you’re going to have angry children, and the process just starts all over again.” When he took a breath, I told him, “I’m Irish on my mom’s side.” He looked surprised, “What does that mean, on your mom’s side? Isn’t your father Irish as well?” I answered, “No, his family came from Wales and Luxembourg.” “What is Luxembourg?” he asked, seeming confused. Remembering that he had to stay in the period of 1620, I answered, “It’s a European country that came about 200 years after your time.” The Irishman spoke his mind, “200 hundred years beyond my time? You cannot know the future. You’re speaking foolish; you must be Irish.” Then he said, “As for your parents, I can’t say anything good about these mixed marriages. Your father should be married to one of his own kind. One shouldn’t challenge the order of nature.” I smiled. Oh how things were different back then. Melissa had gone on ahead of me. “Well, I better go catch up with my wife.” I said to him. “Is she Irish, or Welch?” He asked, “She’s a Swede.” I answered, smiling. “A Swede?” He exclaimed, “It seems your whole family is lacking good sense.” “I’ve been told that before.” I said, laughing and wished him a good day. Walking toward my wife, I noticed how the paint on the deck was badly chipping. Some of the timbers were deteriorating. Wood surfaces were worn. Overall, the 60-year-old boat was in disrepair; rather poor condition. Part of me wished we could see it after the repairs, but then seeing it in its current condition was probably a better example of what the Mayflower really looked like when the pilgrims traveled on it. You have to remember, the Mayflower wasn’t a passenger boat, it was a merchants vessel - a fancy name for a cargo ship. Melissa and I roamed about the deck. The ship seemed much smaller than I would have guessed, but a staff member assured me, “This is the exact same size as the original Mayflower.” The deck wasn’t very large and was reserved for crew who manned the sails and ran the boat under orders from their captain. The galley was in a covered area at the bow of the boat, where meals were prepared for the captain and crew. The passengers were not fed from the kitchen. They had to bring their own food for the journey. At the stern of the ship, on deck level, just below the bridge, was the captain’s and officers’ quarters. They seemed quite simplistic, with a desk, storage areas, and benches for sleeping, but I’m sure they were fancy in their day. We headed below deck, where the pilgrims traveled. Walking down the steps, you felt confined. The ceilings seemed low and it was dark. The walls were unfinished, bare wood. The area wasn’t very large. To put it into perspective, I compared it to the dance hall at a local VFW or American Legion. The passenger area was a fraction of the size. The whole ship was only 80’ long and 24 feet wide. The back of the boat was a restricted area where the crew slept. Space in the bow was gated for livestock. The passengers were squeezed into what seemed like a cargo area, which it actually was. Passengers were only allowed to keep basic necessities with them, including all their food for a journey that lasted over two months at sea. They didn’t have beds or chairs; they slept and sat on the floor. Their other possessions, which were limited, were stored in a cargo pod in the belly of the ship. A staff lady told us, “If the Captain was in a good mood and the seas were calm, he might let five or six people come up on deck for some fresh air. They were only allowed to stay for about ten minutes and not everybody was given time on deck. Most of the pilgrims stayed below deck for the entire trip.” I couldn’t even fathom to guess what that was like. In this small space, 102 people traveled without running water, cooking facilities, heat or bathrooms, for sixty-six days. They lived among livestock in a poorly lit, poorly ventilated space. I can only imagine how bad things must have been in England for these people to be willing to make this journey to an unknown land where they would build a home and make a new life. Again, the experience was very humbling. Our next stop would be Plymouth Colony. A wall made of vertical posts, each carved to a point on top, surrounded the colony. At the entrance there were lookout towers and large gates that were closed to protect the colonist from intruders. We toured though the colony; a village made up of small wooden built homes. Each house had a dirt floor and a thatched roof. The interior walls were coated with a mixture of mud, manure and animal hair, to insulate the structure. A fire pit in one corner was used for cooking and heating the home. The smoke vented through a wooden chimney. I asked one lady, “What happens if your fire goes out?” She looked at me as if I had asked a dumb question, “Why would you let your fire go out?” “I don’t know why, but what if it did?” She said, “Well, I suppose I might impose on a neighbor for a few coals to start another fire, but a woman who lets her fire die out?” She shook her head, “That’s just very poor housekeeping.” A few doors down we met the governor, William Bradford, in his house. His home was about the same size as the others, but better furnished. He had a bed of his own, a wardrobe, a desk for working, a table with chairs for dining and meetings, and an upholstered sitting chair. His floors were also dirt. I asked him about the loft above his house. “Does anyone sleep in the loft?” “Of course not. It’s unlivable. It’s very dusty up there. Why would anyone rest there? It’s only used for storing barrels and extra necessities.” During the course of our conversation he asked, “And from where do you hail?” “Minnesota.” I replied. He was puzzled, “Minnesota? What is Minnesota?” “It’s a state in the Midwest about fifteen hundred miles west of here.” I answered. He was quite concerned, “Another state west of here? Does the King know of this?” He was very serious with his questions, but keep in mind, he could speak only in the period of 1620. “We live on the north shore of Lake Superior.” I told him. “What is Lake Superior?” He asked. I boasted, “The largest fresh water lake in the world.” “You know,” He said, “I’ve heard rumors of a large inland sea to the west. I assumed them to be tall tales, but you’re telling me this sea really exists, and you’ve seen it with your own eyes?” I assured him I had. The governor and I shared more discussion, mostly about government policies and the colony. When we were ready to leave, I extended my hand toward him, saying, “It was a pleasure to meet you, Governor Bradford. I’ve learned a lot from our conversation.” He stared at my hand almost in disbelief. I pushed my hand a little closer to him, saying, “Really, I appreciate you taking time to talk with us. I’d like to shake your hand.” He made a sour face and said, “Well. If such is your custom.” He shook my hand lightly with the tips of his index finger, middle finger and thumb, then quickly pulled his hand away. I thought that was really odd. When we got outside Melissa reminded me, “In the seventeenth century men didn’t shake hands for sanitary reasons. They tipped hats toward one another.” “Oh? Well that explains a lot.” I said and we moved on to the next house. At the next house we met a young lady. Her parents owned the house. She told us in addition to her chores at home, she cooked and cleaned for the Governor to produce extra income for her family. It was money they really needed at that time. She explained, “We’ve taken in a family that just arrived. They had to leave the boat so it could return to England. They will stay with us for the winter. In the spring when the weather breaks, they will build their own house.” “How many people are in the family you’re hosting?” I asked, she answered, “The parents, one daughter and their five boys.” “And how many in your family?” I queried. “I have a sister and two brothers.” she answered. “So there will be fourteen people living in this house for the winter?” She thought for a moment as if she was struggling to add the numbers, and replied, “Yes, I suppose that is correct.” The house we were in when talking to the girl was about ten feet wide and maybe fifteen or sixteen feet long. There was only one bed on the main level. I asked, “Isn’t it kind of crowded? Where does everyone sleep?” “It’s quite cozy,” she said, adding, “The boys sleep in the loft, the adults and the girls sleep down here.” Well, so much for the governor saying, no one sleeps in a loft. Each house had a vertical board fence around the yard to keep their livestock. A smaller fenced area kept the animals out of the garden. Firewood, cut and split, was stacked in a round spiral fashion. A man cutting logs explained by stacking it that way, most of the log ends would be protected from the weather. There weren’t many shops in the village, and the few that were there were in the shopkeepers homes. Every household was self sufficient. They provided everything for themselves. The girl whose family was housing another family told us, “Food will be scarce for the winter. If our supply runs low, some neighbors will help us but that’s only because we are taking in another family in need. Short of that, we would be expected to put up enough food for the winter.” It seemed a very hard life just providing for your family. Every day seemed full, working and preparing for the next winter. Most of the colonists came here for religious freedom. When they weren’t working, religion was a big part of the colonists’ everyday life. I had to wonder just how bad times were in England, that the pilgrims would come here, putting forth such labors, to just barely survive. For all their toils, stock and supplies were limited and yet these people were credited with starting the tradition of giving thanks each fall for the blessings and bounty they had received. I thought about my own ancestors. They were in the colonies less than thirty years after the first pilgrims had arrived. I wondered what caused them to come to the new world? Were there hardships back home they were trying to escape? I pondered just how much they must have wanted a new life, to make the journey. I wondered if they also found winters to be hard; supplies to be limited and if they took part in the early celebrations of giving thanks. This Thanksgiving, as I look over the abundance of food set before me, I will take time to reflect on what we call an abundance, compared to what the pilgrims were giving thanks for. Before I overfill my plate, or overeat, I will take time to consider, “Just how badly do I want this?” Tom can be reached for comment at Facebook.com/tompalen.98

0 Comments

Read More

Leave a Reply. |

Contact Us:

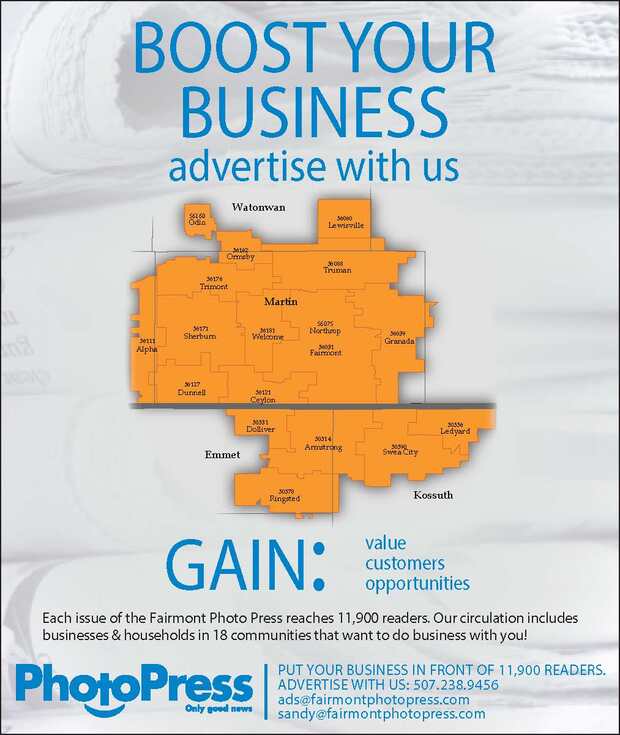

Phone: 507.238.9456

e-mail: [email protected]

Photo Press | 112 E. First Street |

P.O. Box 973 | Fairmont, MN 56031

Office Hours:

Monday-Friday 8:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Phone: 507.238.9456

e-mail: [email protected]

Photo Press | 112 E. First Street |

P.O. Box 973 | Fairmont, MN 56031

Office Hours:

Monday-Friday 8:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed