AuthorThe “FOCUS ON AG” column is sent out weekly via e-mail to all interested parties. The column features timely information on farm management, marketing, farm programs, crop insurance, crop and livestock production, and other timely topics. Selected copies of the “FOCUS ON AG” column are also available on “The FARMER” magazine web site at: https://www.farmprogress.com/focus-ag Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Back to Blog

Since 1970, an annual event called “Earth Day” has been held in late April across the United States. This event has been a time for all U.S. citizens to reflect on our Country’s environmental resources, and what we can do individuals, businesses and as communities to help enhance our environment for the next generation. Many times, farmers and the agriculture industry are portrayed as part of the problem for many the environmental issues that we are facing in the United States. However, in reality the agriculture industry has made some significant advancements in recent decades to help many farmers enhance their environmental efforts.

|

Contact Us:

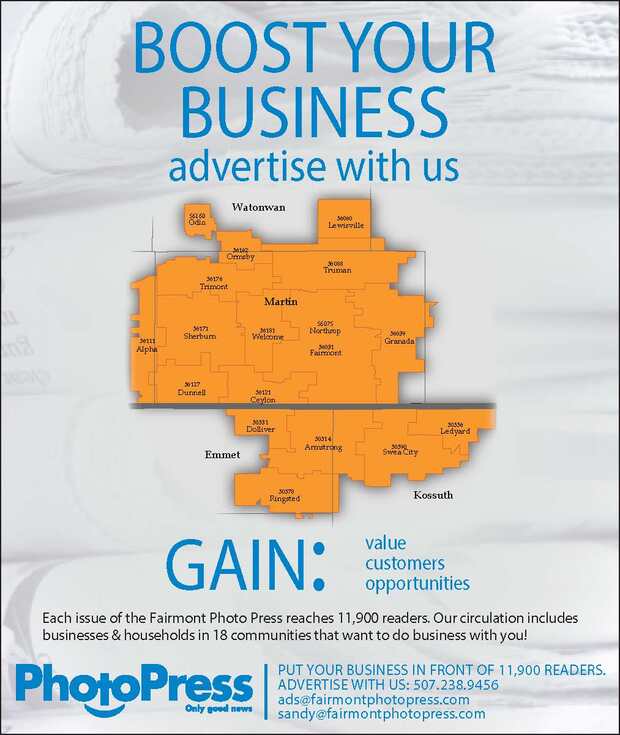

Phone: 507.238.9456

e-mail: [email protected]

Photo Press | 112 E. First Street |

P.O. Box 973 | Fairmont, MN 56031

Office Hours:

Monday-Friday 8:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Phone: 507.238.9456

e-mail: [email protected]

Photo Press | 112 E. First Street |

P.O. Box 973 | Fairmont, MN 56031

Office Hours:

Monday-Friday 8:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed