AuthorThe “FOCUS ON AG” column is sent out weekly via e-mail to all interested parties. The column features timely information on farm management, marketing, farm programs, crop insurance, crop and livestock production, and other timely topics. Selected copies of the “FOCUS ON AG” column are also available on “The FARMER” magazine web site at: https://www.farmprogress.com/focus-ag Archives

July 2024

Categories |

Back to Blog

The excessive rainfall and flooding during June in many portions of the Upper Midwest have created some interesting and in some cases very difficult decisions for several farm operators across the region. A widespread area of Southern Minnesota, Northern Iowa and Eastern South Dakota received 12-16 inches of rain or more during the month of June, which followed more than double the normal precipitation in May. This resulted in flash flooding near rivers and streams and an immense amount of standing water in many areas. The result has been considerable drown-out damage to crops and shallow root systems for crops, as well as loss of nitrogen and other nutrients for the corn crop.

By early July, fields in many areas for farmers to potentially consider replanting some early maturing varieties of soybeans into some of the drown-out areas. Most of the replanting occurred into existing soybean fields that had drown-out damage. Very little replanting occurred on drown-out areas in existing corn fields. Realistically, the best that farmers in the Upper Midwest can hope for with soybeans planted in early-to-mid July is probably a yield of 25-30 bushels per acre, compared to a normal yield of 60 bushels per acre or more. This assumes favorable growing conditions from now until September, as well as the first killing frost not occurring until mid-October. If the replanted soybeans do not produce a crop that can be harvested as grain, they still potentially can make a good cover crop for the drown-out areas. Some farmers were able to get some reimbursement through replant clauses in their crop insurance policies to help cover their replant clauses. Probably the most difficult decisions that farmers in the Upper Midwest have been facing in mid-July are related to the remaining corn crop in the fields that did not drown-out. In many areas, large segments of corn fields have short, yellowish corn with shallow root systems that shows signs of deficiencies of nitrogen and other nutrients. In some cases, portions of these fields may need supplemental applications of nitrogen fertilizer. In addition, wet field conditions can lead to higher incidences of certain corn diseases, which can require fungicide applications. If the remaining corn crop looked fairly viable and we had projected corn harvest prices above $5.00 per bushel, many farmers would probably make the investment into the extra nitrogen fertilizer or applying the fungicide to control the potential corn diseases. However, in many of the worst corn fields in Southern Minnesota, Northwest Iowa, and Southeast South Dakota, the remaining corn crop does not appear to have significant yield potential and the corn harvest price at local grain markets is below $4.00 per bushel. If farmers to choose to apply 30 pounds of extra nitrogen with some sulfur added, the approximate cost would be an estimated $30-$40 per acre. The cost of treating corn with fungicide would likely be an estimated $25-$30 per acre. “Human nature” for most farmers is to try and get the highest corn yield that is reasonably possible, which in a year such as this would probably mean applying the extra nitrogen fertilizer and treating the corn with fungicide, if necessary. However, there is also the economic side of this decision. If a crop producer already feels that his 2024 corn crop may qualify for crop insurance indemnity payments, does it make sense to continue to put discretionary input costs into that crop to get a few more bushels of crop yield ? That decision probably varies from farm-to-farm and field-to-field, so more in-depth analysis may be required before a decision is made. Most farmers carry revenue protection (RP) federal crop insurance policies, which are based on a combination of yield and price. The crop insurance guarantee for a RP policy is the APH yield on a farm unit times the Spring price or base price for a crop times the level of coverage. The 2024 Spring price for corn was $4.66 per bushel, so if a farm had a 200 bushel per acre APH yield with an 85% RP policy, the insurance guarantee would be $792 per acre (200 bu./A. x $4.66/bu. x .85). The harvest value of the crop is the actual yield times the final harvest price for corn, which is the average price of CBOT December corn futures during the month of October. As of July 19, the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) futures price was $4.06 per bushel. If that were the final crop insurance harvest price, crop insurance indemnity payments on a RP policy in corn would begin with a yield loss of approximately 2-3 percent with an 85% RP policy and about 9 percent with an 80% RP policy. With a 200 bushel per acre APH yield, that means that at a $4.06 per bushel harvest price crop insurance indemnity payments would be initiated at a final corn yield below 195 bushels per acre and below 183 bushels per acre with an 80% RP policy. Farmers not only face the difficulty of realistically evaluating the yield potential of the corn remaining in field, but also projecting what likely direction is of the CBOT December corn futures price between now and November. In addition, they need to factor any drown-out acres into the final yield estimates. Another factor that enters into this decision is whether the crop insurance policy insuring the corn is insured under “enterprise units” or “optional units”. Enterprise units combine all acres of a crop in a given county into one crop insurance unit, while optional units allow producers to insure crops separately in each field within a township section. Enterprise units usually have considerably lower premium costs compared to optional units; however, enterprise units are based on larger coverage areas that can make it more difficult to cover crop damage that affect individual farm units. In many instances, corn producers that have insured their crop with optional units will likely be in a better position to fine-tune their decisions regarding added nitrogen or fungicide applications to individual corn fields. If a farm operator has already determined that an individual field in the case of optional unit insurance coverage or all of the corn acres in a county in the case of enterprise units will likely qualify for 2024 crop insurance indemnity payments, then they need to evaluate the potential economic benefits how investing more dollars into crop inputs this growing season. For example, Using the 200 bu./A APH yield with 85% RP policy and a crop insurance harvest price of $4.10 per bushel, a farmer with a final yield of 150 bushels per acre would collect an estimated crop insurance indemnity payment of $177 per acre. If that farmer paid the cost for the extra nitrogen fertilizer and/or fungicide and increased the final corn yield to 180 bushels per acre, the crop insurance indemnity payment would be reduced to about $54 per acre, the added crop value at $3.80 per bushel times 30 bu./A would be $114 per acre, resulting in a total of approximately $168/A. Once the cost of the added nitrogen and fungicide is included, the “net result” would probably close to $125/A., as compared to the insurance indemnity payment without the expense of the added inputs. “One solution doesn’t fit everyone” and every situation is different. The first step is to make a realistic yield estimate of corn field in the case of optional units or all corn acres in a county in the case of enterprise units, factoring in any drown-out or acres with zero production potential. Then find out the cost of any crop inputs and what estimate might be for yield enhancement. A reputable crop consultant or agronomist can assist with evaluating the corn yield potential and benefits from added crop inputs. The next step is to consult with the crop insurance agent regarding the crop insurance coverage level on the 2024 corn crop and what the potential crop insurance indemnity payments would be at various final harvest price levels. It is also good to review your situation with your ag lender before you make the added investment into the corn crop in order to have their input as to how that decision may affect your financial situation with the lending institution. Ultimately, the final decision regarding the investment into more crop inputs for the 2024 corn crop comes down those involved in the business management of the farm operation. If both a husband and wife are involved, or if there are several family members involved, discuss and analyze the situation thoroughly, weighing all the input that was received and the economic analysis that was done. These are challenging mental decisions for farmers, so make it a group decision rather than having the stress of the decision on one individual. Kent Thiesse has prepared an information sheet titled: “2024 Crop Insurance Payment Potential”. To receive a copy, please send an email to: [email protected] Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

The late June USDA Acreage Report is always highly anticipated, because it becomes the first “hard data” after the March USDA Plantings Intentions Report to give an indication of crop production levels for a given growing season. Many times, the June USDA Report can have a big impact on grain market trends, either upwards or downwards, and 2024 is no exception. The crop acreage report was initially viewed “bearish” for corn markets and fairly neutral for soybeans. Based on the June 28th report, farmers planted more acres of corn and less acres of soybeans in 2024 than was projected in the March 30 Planting Intentions Report. USDA surveyed more than 70,000 agricultural producers during the first two weeks of June to gather information for the June 28th report. However, it should be noted that as of early June there was an estimated 3.3 million acres of corn and 12.8 million acres of soybeans remaining to be planted. Crop acreage numbers will be adjusted in future months following the producer acreage reports to Farm Service Agency (FSA) offices in July.

The biggest surprise in the June 28th USDA Acreage Report was the estimate of 91.5 million planted corn acres planted in the U.S. in 2024. This was an increase of over 1.4 million planted acres from the March USDA Planting Intentions Report and was over 1.1 million acres above the estimates of grain marketing analysts. The 2024 corn acreage estimate was a decrease of 3 percent from the 2023 planted corn acres of 94.6 million acres. The estimated 2024 corn acreage also compares to 88.6 million acres in 2022, 93.6 million acres in 2021, 90.8 million acres in 2020, 89.7 million acres in 2019, and 89.1 million acres in 2018. The 2024 corn acreage was increased above the March planting intentions in 6 States, including increases of 600,000 acres in Kansas, 300,000 acres in Iowa, 250,000 acres in Nebraska, 200,000 acres in Minnesota, and 100,000 acres in both Ohio and South Dakota. Based on the June 28th Report, 2024 corn acreage is expected to decrease in 9 of the 12 primary corn producing States, increase in 2 States, and stay the same in 1 State, as compared to 2023 acreage. Following is the estimated 2024 corn acreage in selected Upper Midwest States (with the change from 2023): Iowa at 13.1 million acres (same as 2023); Illinois at 10.9 million acres (down 300,000 acres); Nebraska at 10.1 million acres (up 150,000 acres); Minnesota at 8.1 million acres (down 500,000 acres); Kansas at 6.3 million acres (up 550,000 acres); South Dakota at 6.1 million acres (down 200,000 acres); Indiana at 5.1 million acres (down 350,000 acres); North Dakota at 3.8 million acres (down 250,000 acres); Wisconsin at 3.7 million acres (down 300,000 acres); Missouri at 3.5 million acres (down 350,000 acres); and Ohio at 3.4 million acres (down 200,000 acres). The June 28th USDA Report estimated that 86.1 million acres of soybean acres will be planted in 2024 in the U.S., which was a decrease of 410,000 acres from the March 1st USDA acreage estimate and would be over 650,00 acres below the average estimates of grain marketing analysts. The 2024 U.S. soybean acreage projection does represent an increase of 3 percent or 2.5 million acres from the 2023 planted acres. The estimated 2024 U.S. soybean acreage compares to other recent acreage levels of 83.6 million acres in 2023, 87.4 million acres in 2022, 87.2 million acres in 2021, 83.1 million acres in 2020, 76.1 million acres in 2019, and 89.2 million acres in 2018. The record U.S. soybean acreage was 90.2 million acres in 2017. The 2024 soybean acreage is expected to increase or remain steady in 24 of the 29 reporting soybean producing States, as compared to 2023 acreage, with only Iowa showing a slight year-to-year decline among major soybean producing States. The estimated 2024 soybean acreage in selected Upper Midwest States (with the change from 2023): Illinois at 10.7 million acres (up 350,000 acres); Iowa at 9.9 million acres (down 50,000 acres); Minnesota at 7.6 million acres (up 250,000 acres); North Dakota at 6.8 million acres (up 600,000 acres); Indiana at 5.75 million acres (up 250,000 acres); Missouri at 5.6 million acres (same as 2023); Nebraska at 5.3 million acres (up 50,000 acres); South Dakota at 5.1 million acres (same as 2023); Ohio at 4.85 million acres (up 100,000 acres); Kansas at 4.55 million acres (up 120,000 on acres); and Wisconsin at 2.15 million acres (up 40,000 acres). JUNE 28th QUARTERLY GRAIN STOCKS SUMMARY The USDA Quarterly Grain Socks Report was also released on June 28, which showed the highest inventory of corn stored on farms since 1988. Following is a brief summary of the June 28th Grain Stocks Report: Corn --- The June 28th report indicated a total U.S. corn inventory of just over 4.99 billion bushels on June 1, 2024, which represented an increase of about 22 percent from the corn inventory a year ago on June 1. Approximately 60 percent of the total U.S. corn inventory, or just over 3 billion bushels, was in on-farm storage on June 1, which is up 37 percent from last year at this time. The level of on-farm corn inventories on June 1st included 570 million bushels in Iowa, 460 million bushels in Minnesota, 445 million bushels in Illinois, 250 million bushels in Nebraska, 225 million bushels in South Dakota, 205 million bushels in Indiana, 135 million bushels in Missouri, and 120 million bushels in North Dakota, all of which are well above comparable on-farm inventories in recent years. The June 28th report implied that the estimated total U.S. corn usage from March 1 to May 31 was 3.36 billion bushels, which compares to 3.29 billion bushels during that same time period in 2023. Soybeans --- The Grain Stocks Report showed a total of 970 million bushels of soybeans in inventory as of June 1, 2024, which is an increase of 22 percent from a year ago. It was estimated that 466 million bushels of soybeans, were still in on-farm storage on June 1, 2024, which is up 44 percent from a year ago. This included 83 million bushels in Iowa, 68 million bushels in Minnesota, 66 million bushels in Illinois, 39 million bushels in Ohio, 38 million bushels in Indiana, 37 million bushels in South Dakota, 30 million bushels in Missouri, 18.5 million bushels in Nebraska, and 17.5 million bushels in North Dakota. The level of on-farm soybean stocks on June 1st is significantly higher in many States compared to other recent years. The June 28th report implied that the estimated total U.S. soybean usage from March 1 to May 31 was 875 million bushels, which was down two percent from the same time period a year ago. GRAIN PRICE IMPACTS December corn futures prices on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) fell by 13 cents per bushel following the release of the USDA Crop Acreage and Quarterly Grain Stocks Reports on June 28. The CBOT December corn futures price declined by ten percent or $.47 per bushel during the month of June, which is not a normal early Summer price pattern. This obviously is being driven by the much larger U.S. corn inventory and higher than expected 2024 corn acreage, along with stagnant corn usage and export levels compared to a year ago. The CBOT December corn futures price closed at $4.20 per bushel on June 28. This compares to December CBOT closing futures prices in recent years following the June USDA reports of $4.95 per bushel in 2023, $6.20 per bushel in 2022, $5.54 per bushel in 2021, $3.50 per bushel in 2020, and $4.31 per bushel in 2019. New crop 2024 corn price bids for harvest delivery have dropped below $4.00 per bushel at many locations in the Upper Midwest. CBOT November soybean futures held firm following the June 28th USDA reports and were trading at $11.04 per bushel. Even though the level of soybean stocks in inventory is up from a year ago, the 2024 estimated soybean acreage came in a bit lower than was anticipated by the grain trade. The $11.04 per bushel on June 28 compares to November CBOT closing futures prices in recent years following the June USDA reports of $13.43 per bushel in 2023, $14.10 per bushel in 2022, $13.99 per bushel in 2021, and $8.91 per bushel in 2020, and $9.32 per bushel in 2019. New crop 2024 corn price bids for harvest delivery have dropped below $10.50 per bushel at many locations in the Upper Midwest, with slightly higher bids at soybean processing plants. The stagnant or declining cash and forward contract prices for both corn and soybeans during June is limiting opportunities for farmers to sell remaining grain inventories and to forward price some of the expected 2024 corn and soybean production. Unless there are some weather issues later in the growing season that cut into the anticipated 2024 U.S. crop production, it may be difficult to get any significant increases in corn and soybean price levels between now and harvest-time. Farmers with remaining 2023 corn and soybeans to sell will need to watch for some localized short-term rallies in grain markets to liquidate the remaining inventories before harvest. Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

Back to Blog

Many farmers across the Upper Midwest have been dealing with the impacts of the heavy rains and flooding that have developed in late June. A widespread area of Southern Minnesota, Northern Iowa and Eastern South Dakota received 12-16 inches of rain or more during the month of June, which followed more than double the normal precipitation in May. This has resulted in flash flooding near rivers and streams and an immense amount of standing water in many areas. The result has been considerable drown-out damage to crops, some loss of livestock, and some physical damage to buildings and other property on farm sites. The USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) has announced that there is some assistance available through USDA

Following is some of the assistance that is available through USDA:

All Farmers need to pay attention to FSA and Crop Insurance Deadlines Once the crop is planted and we get into mid-Summer, it is easy to overlook some important deadlines at Farm Service Agency (FSA) offices, crop insurance, and other important deadlines. Missing some of these deadlines can be a costly mistake, as many of the program payments and benefits are linked to compliance with these deadlines. Following is a couple of those important deadlines:

Farm and Rural Stress Assistance The combination of the lowest grain prices in the past five years, together with the likely crop loss from the recent flooding and natural disasters, is likely to result in reduced farm income levels for many farmers in 2024. This is likely to increase the mental stress level for many farmers and farm families. There are some good resources available to assist farm and rural families in the Upper Midwest States that have been impacted:

Website --- https://www.mda.state.mn.us/about/mnfarmerstress

Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

Back to Blog

Few Changes In The June 12 Wasde Report6/19/2024 The USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) Report released on June 12 did not change estimated 2024 corn or soybean production levels and did not make any adjustments in the projected 2024-25 demand levels for either corn or soybeans. The only change in the June WASDE report from the May monthly report was that 2023-24 soybean crush estimates were lowered by 10 million bushels and 2023-24 soybean carryout level was also increased by 10 million bushels. These were no adjustments to the 2022-23 corn usage or carryout levels.

Most grain marketing analysts viewed the June WASDE Report as generally “neutral” for both the corn and soybean market; however, there is some uncertainty with both crops related to estimated 2024 production levels. The supply, production, ending stocks, and price projections in the WASDE Report are for the 2023-24 and 2024-25 marketing years. The USDA marketing year for corn and soybeans for the 2023-24 began on September 1, 2023, and ends on August 31, 2024, and the 2024-25 marketing year ends begins on September 1, 2024, and ends on August 31, 2025. The 2023-24 marketing year USDA marketing year for wheat ended on May 31, 2024, and the 2024-25 marketing year extends from June 1, 2024, to May 31, 2025. Following are some highlights of the June 12th USDA WASDE Report: CORN USDA is projecting 2023-24 corn ending stocks at 2.022 billion bushels, which is the same as the May estimate. The 2023-24 corn ending stocks estimate compares to 1.36 billion bushels in 2022-23, 1.38 billion bushels in 2021-22, 1.24 billion bushels in 2020-21, and 1.92 billion bushels in 2019-20. The projected corn supply for the balance of the 2023-24 marketing year remains quite large in many areas, which is could limit localized support for “old crop” corn prices this Summer. Farmers with some of last year’s corn still in storage will want to watch for rallies in local cash corn bids in the coming weeks to take advantage of the cash corn prices, as well as any short-term improvements in local corn basis levels. USDA kept the projected total estimated 2024 U.S. corn production at 14.86 billion bushels, which was the same as the May WASDE Report. The 2024 estimate compares to the record U.S. corn production level of 15.34 billion bushels in 2023 and other recent production levels of 13.73 billion bushels in 2022, 15.11 billion bushels in 2021, and 14.18 billion bushels in 2020. The projected average U.S. corn yield for 2024 in the June Report is 181 bushels per acre, which is the same as the May estimate. The 2024 yield projection compares to other recent national average corn yields of 177.3 bushels per acre, which was a record yield, 173.3 bushels per acre in 2022, 177 bushels per acre in 2021, 172 bushels per acre in 2020, and 167.4 bushels per acre in 2019. The WASDE Report projects 2024 planted corn acres in the U.S at 90 million acres and harvested acres at 82.1 million acres. This compares to harvested acres of 86.5 million acres in 2023, 78.7 million acres in 2022, and 85.4 million acres in 2021. USDA is estimating total corn usage for the 2024-25 marketing year at just over 14.8 billion bushels, which is 100 million bushels above the projected corn usage levels for the 2023-24 marketing year, and compares to total corn usage of 13.7 billion bushels in 2022-23. Based on the projected U.S. corn acreage in 2024, as well as another record national average corn yield in 2024 and only a modest increase in estimated corn usage, USDA is projecting a slight increase in the corn ending stocks by the end of the 2024-25 marketing year on August 31, 2025, compared to the current marketing year. The 2024-25 corn ending stocks are estimated at 2.102 billion bushels, which would be an increase of 80 million bushels from the estimated 2023-24 corn carryout projections. The projected large corn ending stocks may limit significant rallies in “new crop” corn prices, unless some weather issues develop with the 2024 corn crop. The June 12 WASDE report estimated the average U.S “on-farm” corn price for the 2023-24 marketing year at $4.65 per bushel, which was the same as the May report. USDA also left the 2024-25 corn price estimate unchanged from the May estimate at $4.40 per bushel. The USDA corn price projections for 2023-24 and 2024-25 marketing years are considerably lower than the final national average corn prices of $5.54 per bushel in 2022-23, and $6.00 per bushel in 2021-22. The current corn price projections are more comparable to the final U.S. average corn price of $4.53 per bushel for 2020-21, but are still well above the final average prices of $3.56 per bushel in 2019-20 and $3.61 per bushel in 2018-19. Local cash prices in recent weeks across Southern Minnesota for 2023 corn that is still in storage have been near $4.40 to $4.50 per bushel at many locations. “New crop” corn bids for Fall delivery in 2024 slightly lower than current cash bids at most grain elevators and ethanol plants. SOYBEANS Based on the June 12 WASDE Report, the projected soybean ending stocks for 2023-24 were adjusted 350 million bushels, which was an increase of 10 million bushels from the May report due to the decrease in the soybean crush levels for 2023-24. The estimated 2023-24 soybean ending stocks compare to carryover levels of 264 million bushels in 2022-23, 274 million bushels in 2021-22, 256 million bushels in 2020-21, and 525 million bushels in 2019-20. The preliminary soybean ending stocks for 2024-25 are estimated at 455 million bushels, which is an increase of 30 percent or 105 million bushels from the anticipated 2023-24 carryout levels. USDA did project total soybean usage for 2024-25 at 4.36 billion bushels, which would be an increase of 256 million bushels compared to estimated final 2023-24 soybean usage levels. USDA is estimating the 2024 planted soybean acres at 86.5 million acres and the projected U.S. average soybean yield at 52 bushels per acre, which compare 83.6 million planted acres and a final national average yield of 50.6 bushels per acre in 2023. Some crop experts feel that U.S. soybean acreage could be adjusted in the June 30 USDA Crop Acreage Report, due to the late and prevented planting in some areas of the Northern Corn Belt. Marketing analysts will also be keeping a close eye on the national average soybean yield, which could be highly variable in future months, depending on growing season weather patterns across U.S. soybean production areas. The June 12 WASDE Report listed the projected average U.S “on-farm” soybean price for the 2024-25 marketing at $11.20 per bushel, which is the same as the May estimate. USDA is anticipating the average soybean price for the 2023-24 marketing year, which ends on August 31, 2024, at $12.55 per bushel. The latest USDA soybean price projection for 2024-25 would be well below the projected final 2023-24 national average price and would also trail the final average prices of $14.20 per bushel in 2022-23 and $13.30 per bushel in 2021-22. However, the projected 2024-25 soybean price would still be above other recent average soybean prices of $10.80 per bushel in 2020-21 and $8.57 per bushel for 2019-20. There has not been much movement in cash soybean prices across Southern Minnesota in recent weeks, with prices trading near $11.50 to $12.00 per bushel at processing plants. Basis levels have remained fairly tight due to limited local supplies of soybeans in some areas. Contract prices for Fall delivery of the 2024 soybean crop in Southern Minnesota have been near $10.50 to $11.00 per bushel. WHEAT USDA made no changes in the final 2023-24 wheat demand or carryout numbers in the latest WASDE report. The wheat ending stocks for 2023-24 are projected at 688 million bushels and the 2023-24 farm level price is estimated at $7.00 per bushel. USDA is projecting total 2024 wheat acres at 47.5 million acres and a 2024 U.S. average wheat yield of 49.4 bushels per acre, resulting in a total production level of 1.875 billion bushels. The acreage level was unchanged from the May report and the average wheat yield was increased slightly from 48.9 bushels per acre in May. The final wheat acreage and yield figures will likely be dependent on the late planting dates in the primary spring wheat production areas of North Dakota and Northwest Minnesota, as well as the growing conditions in the Central Plains States. USDA is projecting the 2024-25 wheat ending stocks at 758 million bushels and the estimated 2024-25 U.S. average wheat price at $6.50 per bushel. Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

Back to Blog

Challenging Grain Marketing Decisions6/12/2024 Many farm operators will tell you that making grain marketing decisions is one the most difficult parts of farming. This is especially true during times of stagnant grain markets such as have been occurring in recent months. In July of 2023, December corn futures on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) for the 2023 corn crop were trading above $5.00 per bushel; however, December cash corn futures have not topped that level during the first few months of 2024. In addition, the basis levels at many ethanol plants and grain elevators has widened in 2024 compared to a year ago. As a result, local corn prices being offered for the 2023 corn that is still in storage and being marketed in the Spring and early Summer of 2024 is much lower than it was last year at this time.

Cash corn futures have primarily traded in a range of $4.30 to $4.60 per bushel during the first five months of 2024. Cash corn prices in southern Minnesota at local ethanol plants, feed mills, and grain elevators has primarily ranged from $4.20-$4.50 per bushel in 2024, with some locations across the Midwest temporarily having higher or lower cash corn prices, depending on the local basis levels. Farmers still remember a year ago in 2023, when local cash corn prices in the Upper Midwest were above $6.00 per bushel during the first half of 2023, or 2022, when local cash corn prices in the Midwest traded at $6.50 to $7.50 per bushel during the first half of the year. This drastic change in local corn marketing opportunities has made it difficult for farmers to complete their corn marketing on the 2023 corn that is still in storage and unpriced. Similar to corn, CBOT November soybean futures prices for the 2023 soybean crop were trading above $13.00 per bushel during the early months of the year. By comparison, the cash soybean futures price has remained near $12.00 per bushel during the first five months of 2024 and local soybean basis levels have widened out compared the basis levels last year at this time. Cash soybean prices for unpriced soybeans in storage in southern Minnesota have traded in a range from $11.25 to $11.75 per bushel most of the time during the first few months of 2024, with slightly higher cash prices at soybean processing plants. A year ago, cash soybean prices in the Midwest exceeded $14.00 per bushel on many occasions during the first half of 2023. The much lower cash corn and soybean prices in 2024 in the Spring and early Summer months of 2024, compared to the last few years, has made it very difficult to market the remaining inventory of the 2023 corn and soybean crop that is still in storage. Current cash price offerings for both corn and soybeans during the first half of 2024 have been at lowest level early in the year since the first six months in 2020. Many grain producers had 2023 breakeven levels to cover cash expenses, land costs, and overhead costs of near $5.00 per bushel for corn and over $11.00 per bushel for soybeans, depending on their final crop yields. There have been very few opportunities to capture those price levels since the completion of the 2023 harvest season. For many farmers, the major marketing focus in the past couple of months has turned to trying to “lock-in” favorable prices on the 2024 corn and soybean crop, which has also been very difficult. The “new crop” CBOT December corn futures has traded in a fairly tight range of $4.60 to $4.80 per bushel most of the time since January of 2024, only briefly reaching $4.90 per bushel on a few occasions. Local ethanol plants and grain elevators in Southern Minnesota have typically been offering forward contract corn prices for harvest delivery of the 2024 crop in the $4.25-$4.50 per bushel range during the past few months, which is about $1.00 per bushel lower than “new crop” cash corn bids a year ago at this time in 2023, and $2.00 per bushel below harvest price bids in the Spring months of 2022. Basis levels for “new crop” corn have generally been $.30-$.40 per bushel below the CBOT December corn futures price at most locations in the Upper Midwest, with some variation depending on location. This is a much wider basis level than existed in the previous couple of years in early June. Like corn, the 2024 “new crop” CBOT November soybean futures price has traded much lower during the first few months of 2024, compared to futures prices during similar months in recent years. The November soybean futures price has generally traded between $11.50 and $12.00 per bushel in the first five months of 2024. By comparison, the harvest futures price in the first few months of 2023 was trading above $13.00 per bushel, and was above $14.00 per bushel in 2022. The basis level for 2024 “new crop” soybeans in the Upper Midwest generally been $.70-$.80 per bushel below the CBOT November futures price in recent weeks, and $.40-$.50 per bushel below at soybean processing plants. This 2024 soybean basis levels are significantly wider than typical pre-harvest basis levels that were offered in the three previous years. Local “new crop” cash prices in the Upper Midwest for the 2024 soybean crop have generally been in the $11.00 to $11.50 per bushel range, with prices exceeding or dropping below that level a few times, depending on location and local basis levels. Price offerings at processing plants have been slightly higher. Looking ahead to grain marketing opportunities in the Summer months of 2024 Prior to the 2024 planting season in March and early April this year, there was considerable concern about the potential for drought during the 2024 growing season in the Upper Midwest. However, above normal precipitation in the past two months has basically eliminated drought concerns in the primary corn and soybean production areas in the country. USDA released the first crop ratings for the 2024 corn crop on June 3, which showed 75 percent of the U.S. corn crop rated “good to excellent”. This compares to a “good to excellent” rating of 69 percent a year ago in early June and a 5-year average of 70 percent. The only recent year to exceed the initial 2024 corn rating was at 76 percent in 2021. Nearly all major corn producing States in the Upper Midwest had an initial 2024 corn crop rating between 70 to 80 percent in the “good-to-excellent” category. In the past few decades, when the initial crop rating has exceeded the previous average, the resulting U.S. corn yield has reached a record yield level about 50 percent of the time. The current record U.S. corn yield is 177.3 bushels per acre, which was set last year, even though there were very dry conditions in portions of the Upper Midwest in 2023. USDA is currently projecting a trendline corn yield of 181 bushels per acre in 2024 and most grain marketing analysts are estimating the national 2024 U.S. corn yield between 178 and 180 bushels per acre. In any case, unless drought or some other weather issue develops later this year, there will likely be a very solid U.S. corn yield in 2024, which will likely keep U.S. corn ending stocks at fairly high levels and put downward pressure on “new crop” corn prices. The initial 2024 soybean crop rating will be released in the June 10th weekly USDA crop progress report. Most analysts also expect the initial soybean crop rating for this year to exceed the 5-year average rating, with fairly solid ratings in most of the major soybean producing States. The USDA crop progress report on June 3 listed soybean planting in the U.S. at 78 percent completed, which was five percent ahead of the 5-year average. The soybean planting progress has been a bit slower in some portions of the Upper Midwest due to excess rainfall during late May and early June. About the only thing that could be a positive for the “new crop” soybean prices would be if the final soybean planted acres are below the expectations of USDA and grain marketing analysts, or if negative weather conditions develop later this Summer. Making grain marketing decisions for 2023 grain that is still in storage, as well as for this year’s corn and soybean crop, has been very challenging during the first few months of 2024. Most farmers probably have a 2024 “breakeven” market price of over $5.00 per bushel for corn and over $11.00 per bushel for soybeans to cover crop input expenses, land costs, and overhead expenses at average crop yields. There have not been very many opportunities to “lock-in” local cash prices at or above those levels in recent months. Unless drought conditions or other crop production problems develop later in the 2024 growing season, it is not likely that there will be a major rally in corn and soybean prices later this Summer. In the absence of weather issues, corn and soybean prices in 2024 are likely to follow a more typical seasonal price pattern as we progress toward harvest. Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

Back to Blog

There has finally been some movement on potential approval of a long-awaited new Farm Bill. In mid-May, U.S. House Agriculture Committee Chairman, Congressman Glenn (GT) Thompson (R-PA) released the text for the initial version of the U.S. House Farm Bill, which is titled: “Farm, Food and National Security Act of 2024”. The version of the House Farm Bill has generally been viewed as “farmer-friendly” by some ag policy analysts; however, there have been negative reviews from some members of Congress and by some organizations. The entire U.S. House Agriculture Committee approved the initial House Farm Bill on May 24; however, only 4 Democratic members on the committee supported the House Farm Bill. The U.S. Senate Agriculture Committee has also released some initial provisions likely to be included in the Farm Bill.

• The 2023 crop year was set to be the final year for the 2018 Farm Bill; however, the Farm Bill was extended for the 2024 federal fiscal year and is now set to expire on September 30, 2024. Farm Bills are one of the most comprehensive pieces of legislation that are passed by Congress, with programs ranging from farm commodity programs to food and nutrition programs, from conservation programs to rural development programs, and several more. In many cases, finalizing a Farm Bill can be quite controversial, both along political party lines and geographical differences, with members of Congress wanting to protect the farm, food, conservation, and economic interests of their State. • Following are some initial details for commodity programs and crop insurance from the new Farm Bill proposal that was passed by the U.S. House Ag Committee: – Increases the “statutory reference prices” (SRP) for all commodities by 10 to 20 percent. The SRP sets the minimum reference price for farm program commodities that is used to calculate price loss coverage (PLC) and ag risk coverage (ARC) program payments. It would increase the statutory reference price for corn to $4.10/bu., soybeans to $10.00/bu., and wheat to $6.35/bu. – The formula to calculate the “effective reference price (ERP) would be continued in the next Farm Bill. The ERP is calculated by taking 85 percent of the national market year average (MYA) price of the five years previous to the year preceding the current program year, dropping the high and low price, and averaging the other three years. The final ERP each year is the higher of the calculated price and the statutory reference price. – Increases the ARC guarantee to 90 percent of the benchmark revenue (currently 86 percent) for both the county-yield based ARC-CO program and the individual yield based ARC-IC program. It would also increase the maximum ARC payment to 12.5 percent of the ARC revenue (currently 10 percent). – Increases the marketing assistance loan (MAL) rates for most commodities. – Provides an opportunity to add new crop base acres for farms that currently have no base acres or that have been planted to more acres of program crops than the existing base acres. This provision would not affect existing crop base acres but would be in addition to those base acres. – Would increase the farm program payment limit to $155,000 for any eligible individual earning at least 75 percent of their income from farming (currently at $125,000) and this payment limit would be indexed to inflation going forward. Would also adjust payment limit language to be comparable for farm LLC business structures as currently exists for farm general partnerships. – Would increase the supplemental crop option (SCO) crop insurance coverage up to 90 percent of the county yield times the spring crop insurance price (currently the SCO coverage is at 86 percent). The cost of SCO coverage would be subsidized by the federal government at 80% (currently 65%). – Would also enhance “whole-farm” revenue protection crop insurance products and provide added crop insurance options for specialty crops. Initial U.S. Senate Farm Bill proposals for the commodity and crop insurance titles …... Senator Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), Chair of the U.S. Senate Agriculture Committee, has not released the official text for the Senate Farm Bill; however, some initial likely provisions have been released. Here are some of those likely commodity and crop insurance title provisions from the Senate Farm Bill proposal: – Maintains the current PLC and ARC program choice for eligible commodities and keeps the formula for payment acres the same as the current Farm Bill. – Increases the minimum statutory reference prices (SRP’s) for all farm program commodities by 5 percent and continues the formula for calculating the effective reference prices (ERP). – Would establish a maximum PLC payment rate at 20 percent of the reference price for a commodity. Currently the maximum PLC payment rate is the difference between the reference price and the marketing loan rate for that commodity. For example …… the 2024 corn reference price is $4.01 per bushel and national corn loan rate is $2.20 per bushel, so the maximum PLC protection is $1.81 per bushel; however, under the proposed Farm Bill the maximum would be reduced to $.80 per bushel. – Increases the ARC program guarantee to 88 percent of the benchmark guarantee (currently 86%) but would continue the maximum ARC payment at 10 percent of the benchmark guarantee. – Provides limited opportunity for underserved farmers to update crop base acres and establish farm program yields. This would differ from the broader base acre update proposal in the House Farm Bill, – Marketing assistance loan (MAL) rates for eligible commodities would be indexed to the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) five-year cost of production for a given commodity. – Would restrict commodity program payments from being made on land owned by individuals or legal entities with an adjusted gross income (AGI) exceeding $700,000. If is not clear how this might impact farm program eligibility for farm operators that rent farm land from individuals exceeding that limit. – Enhances crop insurance premium subsidies for beginning farmers in their first ten years of farming. – Increases the SCO crop insurance coverage to 88 percent (currently 86%), similar to maximum ARC farm program coverage and expands SCO coverage to more crops. The SCO federal premium subsidy would increase to 80 percent of the insurance premium (currently at 65 percent). • As can be seen, there are some differences in the commodity and crop insurance proposals in the U.S. House and Senate versions of a new Farm Bill; however, most of those differences could likely be worked out through the conference committee process. The Senate Farm Bill would greatly expand many of the programs in the conservation title of the Farm Bill and links many of those programs to the so-called “climate-smart” agricultural practices that have been identified through the climate programs that are being initiated through the climate funding in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) that was passed in 2023. The Senate Farm Bill also would not place any restrictions on eligibility for SNAP and other programs under the nutrition title of the Farm Bill, while the House Farm Bill would place some restrictions on certain aspects of these programs. The biggest difference may likely come down to how the funding is allocated in the Farm Bill. The proposed House Farm Bill would significantly increase spending for commodity programs and crop insurance, while the Senate Farm Bill would likely add more spending to the conservation and nutrition titles of the Farm Bill. • The initial release of some details for the new Farm Bill and the action by the U.S. House Agriculture Committee has provided some optimism regarding the completion of a Farm Bill by the end of 2024; however, many steps remain to complete that process. Once a Farm Bill is approved by both houses of Congress, a conference committee will need to work differences in the House and Senate versions of the Farm Bill and have it re-approved in both houses of Congress, before ultimately sending it to the President for final approval. This will likely need to happen by the end of 2024 or very early in 2025 to make it possible for the new legislation to be implemented for the 2025 crop year. Ultimately, a compromise will likely be reached and a new 5-year Farm Bill will be passed; however, given the political division that currently exists in Congress, this may be difficult to accomplish in 2024. As a result, another one-year extension of the current Farm Bill for 2025 is certainly a possibility. Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

Back to Blog

The University of Minnesota recently reported that the average net farm income for Southern and West Central Minnesota farmers in 2023 was $76,181, which was a sharp decline from the 2022 average net farm income of $311,240. The 2022 net farm income was the highest average net farm income ever recorded in the FBM Summary. The 2023 average net farm income was at the lowest level since 2018 and followed three years (2020-2022) of very strong net farm income levels in the region. The reduction in net farm income levels in Southern and West Central Minnesota were largely driven by reduced crop profits that resulted from much lower grain market prices than 2021 and 2022, along with reduced crop yields in some locations. Livestock profit margins in 2023 in Southern Minnesota were mixed, showing strong profits in beef production but very modest or negative profit margins in dairy and hogs.

The Farm Business Management (FBM) Summary for Southern and West Central Minnesota is prepared by the Farm Business Management Instructors. This summary includes an analysis of the farm business records from farm businesses of all types and sizes in Southern and Western Minnesota. This annual farm business summary is probably one of the “best gauges” of the profitability and financial health of farm businesses in the region on an annual basis. Following are some of the key points from the data in the 2023 FBM Summary: BACKGROUND DATA · The “Net Farm Income” is the return to labor and management, after crop and livestock inventory adjustments, capital adjustments, depreciation, etc. have been accounted for. This is the amount that remains for family living, non-farm capital purchases, income tax payments, and for principal payments on farm real estate and term loans. The average net farm income in 2023 was +$76,181. · The “median” net farm income is the midpoint net farm income of all farm operations included in the FBM Summary, meaning that half of the farms have a higher net farm income and half have a lower net income. The average median net farm income in 2023 was only +$40,039. · A total of 1,590 farms from throughout South Central, Southwest, Southeast, and West Central Minnesota were included in the 2023 FBM Summary. The average farm size was 687 crop acres. The top 20 percent net income farms averaged 1,188 acres, while the bottom 20 percent net income farms had 845 acres. · 62 percent of the farm operations were cash crop farms and 12 percent were single entity livestock operations, with the balance of farms being various combinations of crop, livestock, and other enterprises. · 883 farms (55%) were under $500,000 in gross farm sales in 2023; 354 farms (22%) were between $500,000 and $1 million in gross sales; 263 (17%) were between $1 million and $2 million in gross sales; and 89 farms (6%) were above $2 million in gross sales. · In 2023, the average farm business received only $624 in crop-related government program payments. Livestock-related government payments averaged $9,193, which was largely due to very large Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program payments to dairy producers. CRP and conservation payments averaged $1,932. The average level of government payments received by farm businesses has been greatly reduced in recent years compared to levels from 2018-2020. · The average family living expense in 2023 was $78,182, which increased slightly compared to recent years. The average non-farm income in 2023 was $47,214, which represents about 32 percent of total annual non-farm expenses ($151,739) by families for family living and other uses. · In 2023, the average farm business spent $1,298,802 for farm business operating expenses, capital purchases, and non-farm expenses. The total dollars spent by the 1,590 FBM farm families was nearly $2.1 billion. Most of this money was spent in local communities across the region, helping support the area’s overall economy. FARM FINANCIAL ANALYSIS · The average net farm income for Southern and West Central Minnesota for 2023 was $76,181, while the median net farm income for the region was $40,039. This compares to median net farm income levels of $177,614 in 2022, $176,426 in 2021, $102,848 in 2020, $36,547 in 2019, and $20,655 in 2018. · As usual, there was large variation in median farm income in 2023. The top 20 percent profitability farms averaging a median net farm income of +$288,243, which was down from +$728,237 in 2022. The low 20 percent profitability farms with an average median net farm income of negative ($96,605), down from +$13,238 in 2022. · The variation in median net farm income in 2023 also showed some differences based on the gross receipts of the farms. Farms with $1.5 to $2 million in gross receipts had a median net farm income of +$107,644, compared to +$135,680 for farms with a gross of $1 to $1.5 million, +$63,356 for farms with a gross of $500,000 to $1 million, +$38,319 for farms with a gross of $250,000 to $500,000, and +$26,235 for farms with a gross of $100,000 to $250,000. Interestingly, when you look at the profit margin, the smaller volume income groups actually had a higher margin. The $100,000 to $250,000 group was at 31.4% profit margin, the $250,000 to $500,000 group at 26.1%, the $500,000 to $1 million group at 14.5%, the $1 to $1.5 million group at 16.2%, and the $1.5 to $2 million group at 14.2% profit margin. · The average farm business showed working capital of +$469,185 in 2023, which is down 22 percent from 2022 levels but is still 2.5 times higher than the average working capital in 2019. The current ratio (current assets divided by current expenses) for 2023 was 231%, which compares to 283% in 2022, 247% in 2021, 198% in 2020, and 156% in 2019. The working capital to gross revenue ratio for 2023 was 44.5%, which is still at a very strong level compared to the much more challenging levels in 2018 and 2019. · Another measure of the “financial health” of a farm operation is the “term debt coverage ratio”, which measures the ability of farm operations to generate adequate net farm income to cover the principal and interest payments on existing real estate and term loans. If that ratio falls below 100%, it results in the farm business being required to use working capital or non-farm income sources to cover the difference. The average term debt coverage ratio for 2023 dropped considerably to a level of 125%, which was the lowest since 2018. This compares to average ratios of 372% in 2022, 389% in 2021, 274% in 2020, and 148% in 2019. The bottom 40 percent profitability farms had an average term debt coverage ratio below 100% in 2023. · The overall solvency of the 1,590 farm businesses in the FBM program have remained fairly stable in recent years. The average debt/asset ratio in 2023 was 43%, which was has been nearly steady for the past four years. The debt/asset ratio for the lowest 20 percent profit farms was 49% and was 38% for the 20 percent highest profit farms. The average farm listed just over $3 million in total farm assets, just over $1.14 million in farm liabilities, for an average farm net worth of approximately $1.8 million. BOTTOM LINE Overall, net returns from crop operations in 2023 were down considerably from the very strong farm profit levels in 2022 and 2021. As usual, there was a wide variation in farm profit levels from the top one-third of net farm income operations as compared to other farms. The overall average financial health of most farm businesses remains quite solid due to strong working capital and cash surpluses from 2021 and 2022. The reduced net farm income levels in 2023 point to some “caution flags” on the horizon for farm profitability. These include rapidly continued high input expenses and land costs, continued sluggish grain prices, and inconsistent livestock profitability. Complete farm business management results are available through the University of Minnesota Center for Farm Management FINBIN Program at: https://finbin.umn.edu/ Note --- For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone --- (507) 381-7960; E-mail --- [email protected]

Back to Blog

The USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) Report released on May 10 projected strong production levels in 2024 and a likely increase in corn and soybean ending stocks by the end the 2024-25 marketing year on August 31, 2025. U.S. wheat stocks are also expected to increase in the coming year. From a grain marketing standpoint, the initial reaction to the WASDE report was positive for corn and soybeans in the short-term; however, USDA is projecting that the national average grain prices for corn, soybeans, and wheat will all decline by the conclusion of the 2024-25 marketing year, compared to 2023-24 price levels. Following are some highlights of the latest USDA WASDE Report:

Corn: Based on the May 10 USDA WASDE Report, the projected corn ending stocks for the 2023-24 marketing year are estimated at 2.022 billion bushels, which is a decrease of 100 million bushels from the April Report, due to expected increases in both corn exports and corn used for ethanol production of 50 million bushels each. The anticipated 2023-24 corn ending stocks still represent a substantial increase from 1.36 billion bushels in 2022-23, 1.38 billion bushels in 2021-22 and 1.23 billion bushels in 2020-21. USDA is projecting that total U.S. corn usage for 2023-2024 at just over 14.7 billion bushels for livestock feed, ethanol, exports, etc., which is an increase of 7.2 percent or 1 billion bushels compared to the 2022-23 usage level. The higher estimated corn usage was mainly due to increases in the estimated amount of corn used for feed, ethanol production, and exports in 2023-24, compared to a year earlier. The 2023-24 corn stock-to-use ratio is now estimated at 13.7 percent, up from 9.9 percent in 2022-23 and 9.2 percent in 2021-22. The May WASDE Report also offered an initial USDA estimate for corn carryover levels in the 2024-25 marketing year, which ends on August 31, 2025. The corn ending stocks were estimated at 2.1 billion bushels, which would be an increase of about 100 million bushels compared to the end of the 2023-24 marketing year. The 2024-25 stocks-to-use ratio is expected to increase to 14.2 percent. The projected 2024-25 the carryout level would be the highest since the end of the 2016-17 and the ending stocks were near the average grain-trade estimates. USDA is estimating the total corn supply for 2024-25 at 16.9 billion bushels and the total corn usage for the year at 14.8 billion bushels. USDA is forecasting a slight increase in corn usage for livestock feed and higher U.S. corn export levels, as well as stable corn usage for ethanol production in 2024-25. USDA is estimating total U.S. corn production in 2024 at 14.86 billion bushels, which would be down 3.1 percent from the record 2023 U.S. corn production of 15.34 billion bushels. The USDA Report expects an estimated 90 million acres of corn to be planted in the U.S. in 2024, which compares to 94.6 million acres in 2023 and 88.2 million acres in 2022. USDA is projecting the average U.S. corn yield at 181 bushels per acre in 2024, which is up from the record average yield of 177.3 bushels per acre in 2023, as well as the 2022 yield of 173.4 bushels per acre. The WASDE corn yield estimate is very close to the trend line corn yield forecast at the USDA Ag Outlook Conference in February this year. Corn planting progress in 2024 has been running near normal in many areas of the central and northern Corn Belt of the U.S., but is behind normal in some areas of the eastern Corn Belt. As of May 10, USDA is estimating the average U.S “on-farm” corn price for the 2023-24 marketing at $4.65 per bushel, which was down $.05 per bushel from the April estimate. The current USDA projected corn price compares to recent final national average prices of $6.54 per bushel for 2022-23, $6.00 per bushel for 2021-22, $4.53 per bushel for 2020-21, and $3.56 per bushel for 2019-20. USDA also released the first estimated average corn price for the 2024-25 marketing year at $4.40 per bushel, which would be $2.14 per bushel lower than the final 2022-23 national average price, which represents a decline of 33 percent in two years. Soybeans: Based on the May 10 WASDE Report, the projected soybean ending stocks for 2023-24 are estimated at 340 million bushels, which is the same as the April estimate and was close to the average grain trade estimates. The projected 2023-24 soybean ending stocks have widened a bit compared to other recent soybean carryover levels of 264 million bushels in 2022-23, 274 million bushels in 2021-22, and 257 million bushels in 2020-21. The projected ending stocks are still well below 525 million bushels in 2019-20 and 909 million bushels in 2018-19. Total soybean usage for 2023-24 is estimated to be just over 4.11 billion bushels, which is down slightly from the total usage of 4.30 billion bushels in 2022-23. Soybean export levels for 2023-24 are projected to decrease by 292 million bushels compared to a year earlier. USDA projected a slight increase in bushels used for soybean processing in the U.S for 2023-24 compared to crush levels a year earlier. Some analysts feel that domestic soybean demand may increase in the next few years with several new or expanded soybean processing plants scheduled to come on board, focusing on the production of renewable diesel. The May WASDE Report projects soybean ending stocks to increase by 105 million bushels to 445 million bushels by the end of the 2024-25 marketing year on August 31, 2025. USDA is estimating the total U.S. soybean supply to increase by 285 million bushels in 2024-25; while the total soybean usage is expected to increase by 246 million bushels compared to levels for 2023-24. The projected ending stocks-to-use ratio for 2024-25 is estimated at 10.2 percent, which compares to 8.2 percent in 2023-24 and 6.1 percent in 2022-23. Total U.S. soybean production in 2024 is estimated at 4.45 billion bushels, which would be an increase from the estimated U.S. soybean production of 4.16 billion bushels in 2023 and 4.27 billion bushels in 2022. Interestingly, a year ago in May USDA projected the 2023 U.S. soybean production at 4.51 billion bushels and the actual 2023 production was 345 million bushels less. Planted soybean acres for 2024 are projected at 86.5 million acres, which is up from 83.6 million acres in 2023, but lower than 87.5 million acres in 2021. USDA is estimating a national average soybean yield of 52 bushels per acre in 2024, which compares to 50.6 bushels per acre in 2023 and 49.6 bushels per acre in 2022. The record U.S. soybean yield was 52.1 bushels per acre in 2016. USDA is estimating the U.S “on-farm” soybean average price at $11.20 per bushel for the 2024-25 marketing year, which runs from September 1, 2024 to August 31, 2025. The preliminary price estimate for the 2024-25 marketing year would represent a 21 percent decline or $3.00 per bushel from the market year average price on May 1st two years ago. The projected final market year average price for 2023-24 is $12.55 per bushel soybean price, which compares to final average soybean prices of $14.20 per bushel in 2022-23, $13.30 per bushel for 2021-22, and $10.80 per bushel for 2020-21, and $8.57 per bushel for 2019-20. The average soybean prices for 2024-25 will likely be highly dependent on 2024 soybean production in the U.S. and South America, as well as increases in soybean crush levels and the amount of U.S. soybean exports to China and other countries. Wheat: The May 10 WASDE Report projected U.S. wheat ending stocks to increase by 78 million bushels to 766 million bushels by the end of the 2024-25 marketing year on May 31, 2025. This compares to estimated ending stocks of 688 million bushels for 2023-24 and 570 million bushels in 2022-23. Wheat demand in 2024-25 is projected to increase slightly from the current year demand up to 1.9 billion bushels, with the increase mainly due to higher export estimates. Wheat acreage in 2024 is expected to decrease to 47.5 million acres; however, total U.S. wheat production is expected to increase slightly in 2024 to 1.86 billion bushels. Wheat acreage and production numbers could be adjusted in coming months, depending on planting conditions in the primary spring wheat production region. USDA is projecting the average “on-farm” wheat price at $6.00 per bushel for 2024-25 and $7.10 per bushel for 2023-24, which compares to other recent final national average price of $8.83 in 2022-23, $7.63 per bushel in 2021-22 and $5.05 per bushel in 2020-21. Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

Back to Blog

Spring fieldwork got off to a good start in many portions of the Upper Midwest in mid-April; however, conditions have been much different in late April and early May. Frequent rainfall events and above normal precipitation have kept most farmers out of the field since late April. In some areas, it may take several drier days in order to return to full-scale fieldwork, and the resulting soil conditions may be less conducive for good planting conditions. In addition, except for a few brief stints of some warmer temperatures, very cool and cloudy weather conditions have existed throughout the region in the past couple of weeks. This has slowed germination and emergence of the corn and soybeans that were planted prior to the prolonged rainfall events. Some standing water and flooding has occurred in areas that have received high amounts of rainfall and near small rivers and streams. This may require replanting of crops in some of these areas.

Some portions of the Upper Midwest had very good corn and soybean planting progress in mid-April. Farmers in some areas were able to take advantage of some brief planting windows that existed from April 12-15 and again from April 21-25. As a result, portions of the region, such as South Central and Southwest Minnesota and Northern Iowa, have 80-90 percent of the corn and 30-40 percent of the soybeans planted, while other areas of the region have very little crop planted. Normally by early May, Midwest farmers have made some significant planting progress on Spring fieldwork. For farm operators that were able to plant some corn during April, there has been some concern about the seedling viability of that corn due to the extended period cool and damp soil conditions that has existed across the region. The good news is that the weather forecast for mid- May appears to be much more favorable for corn and soybean development in most areas of the Upper Midwest. The USDA Weekly Planting Progress Report released on April 29 indicated that 27 percent of the intended U.S. corn acreage for 2024 was planted by that date. This compares to the 5-year average of 22 percent of the corn planted by that date. As of April 29, Minnesota had 30 percent of the corn planted, compared to a 5-year average of 18 percent, while Iowa had 39 percent planted, compared to a 5-year average of 28 percent planted. Other States that were ahead of the 5-year average in corn planting progress on April 29 included Missouri at 63 percent, South Dakota at 13 percent, Wisconsin at 10 percent, and North Dakota at 6 percent. Illinois and Nebraska were both near the 5-year average for corn planting progress at 25 percent and 22 percent, while Indiana and Ohio were behind the normal pace for corn planting with less than 10 percent planted in both States. As of April 29, 18 percent of the U.S. soybeans had been planted, compared to the 5-year average of 10 percent planted by that date. One piece of good news for farm operators in many portions of the Upper Midwest is that recent rainfall events have helped ease drought concern for the early portions on the 2024 growing season. Many areas of the primary corn and soybean production areas in the Upper Midwest were listed as “abnormally dry” to “severe drought” in the weekly U.S. Drought Monitor entering the month of April. However, frequent rainfall events and above normal precipitation during April have either eliminated or greatly shrunk to drought concern area in the weekly update. There should now be adequate soil moisture this year for good corn and soybean germination and early season plant growth in most areas of the Upper Midwest. In addition, the amount of stored soil moisture in the top 5 feet of soil has now been restored to much improved levels, compared to the soil moisture conditions that existed after harvest in 2023 and in early Spring this year. The University of Minnesota Research and Outreach Center at Waseca, Minnesota, recorded 4.53 inches of rainfall during April, which was 1.23 inches above normal, and has recorded over two inches of additional precipitation during the first few days of May. This followed several months of below normal precipitation at the Waseca site. The total precipitation for 2024 at the Waseca site is now near normal. The good news is that most rainfall events were not extreme and have left the soil conditions very favorable for early season plant growth. Soil temperatures at the Waseca site were well above normal in mid-April; however, have dropped below normal by early May. The average soil temperature at the 2-4 inch level on April 15 at the Waseca research location was above 55 degrees Fahrenheit (F), which is almost ideal for good corn and soybean planting conditions. After briefly dropping below 50 degrees F, the average soil temperatures have remained in the 50-55 degree F range during most of late April and early May. Research has shown that 50 percent corn emergence will occur in 20 days at an average soil temperature of 50 degrees F, which is reduced to only 10 days at an average temperature of 60 degrees F. This may help explain why some of the corn that was planted 2-3 weeks ago has been quite slow to emerge. The good news is that temperatures are predicted to get warmer in the next couple of weeks. Even though planting dates have been delayed in many areas of the Upper Midwest, most University and private agronomists are encouraging producers to be patient with initiating field work, and to wait until soil conditions are fit for good corn planting and seed germination. Given the high cost per acre of seed corn, and the limited availability of some of the best yielding corn hybrids in 2024, most growers do not want to take the risk of planting corn into poor soil conditions. Normally, in mid-May, the soil temperatures warm up quite rapidly, so concern over cool soil temperatures becomes less of an issue. It is expected that full-scale corn and soybean planting will resume as soon as the field conditions dry out and are fit for planting. Timely corn planting in the Upper Midwest is usually one of the key factors to achieving optimum corn yields in a given year. According to research at land-grant universities and by private seed companies, the “ideal time window” to plant corn in Upper Midwest in order to achieve optimum yields, if soil conditions are fit for planting, is typically from about April 15 to May 10. Based on long-term research, the reduction in optimum corn yield potential with planting dates from May 10-15 in many areas of the region is usually very minimal and is quite dependent on the growing season weather that follows. Even corn planted from May 15-25 has a good chance of producing 90-95 percent of optimum yield potential, assuming that there are favorable growing conditions following planting. The ideal window to plant soybeans in the Upper Midwest and to still achieve optimum yields starts in late April and extends until mid-May or even beyond in some years, so there is still ample time to get the 2024 soybean crop planted. Even though corn planting is off to very slow start in some areas in 2024, compared to other years, the good news is that there are still opportunities for timely planting and close to optimal yields. In both 2022 and 2023, a large amount of corn in the Upper Midwest was planted in mid-to-late May. Minnesota achieved a record state average corn yield of 195 bushels per acre in 2022 and ended with a statewide yield of 185 bushel per acre in 2023, which probably would have been higher had it not been for drought conditions late in the growing season in portions of the State. On the other hand, the corn planting dates were also delayed in the 2019 crop year in many portions of Minnesota, when the statewide average corn yield was only 173 bushels per acre, which was the lowest statewide corn yield in recent years. The biggest difference in those years was that the growing conditions after planting in 2022 and 2023 were almost ideal in many areas from late May until early July. By comparison, the 2019 corn crop was planted late into poor soil conditions, which was followed by less-than-ideal conditions throughout much of the growing season. Most farm operators in the Upper Midwest will likely not switch intended 2024 corn acres to soybeans unless the corn planting dates get extended into late May or beyond. By April, producers have typically finalized decisions for seed, fertilizer, and other crop inputs for the growing season, so they are likely to continue with their planned crop rotations as long as possible. In addition, there is not currently a big advantage in the projected market price at harvest this year for either corn or soybeans. New crop corn and soybean prices for the Fall of 2024 have remained fairly low in recent months due to weaker than expected demand and export volume, together with USDA projecting increases in corn and soybean inventories by the end of 2024. Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected]

Back to Blog

Many crop producers in the Midwest were enrolled in the Ag Risk Coverage (ARC-CO) farm program choice on their corn and soybean base acres for the 2023 crop year. With the advent of much lower corn and soybean market prices since the 2023 harvest season, many farmers are now wondering if there will be any 2023 ARC-CO payments for corn and soybeans for the 2023 crop year. Producers have a farm program choice each year on all eligible crops between the Ag Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) farm program choices. Any potential ARC-CO or PLC payments for the 2023 crop year would be paid to producers in October of 2024.

The PLC program payments are “price-only” and are based on comparing the 12-month national market-year average (MYA) price for a given crop compared to the established reference price for that year. If the 12-month average price is lower than the reference price, the producer would earn a PLC payment for that year. Enrollment in the PLC program has been fairly low in recent years due to corn and soybean commodity prices that have been well above the established PLC reference prices. The ARC-CO farm program choice includes a formula that uses 5-year average county-based yield calculations and 5-year average MYA prices to establish a benchmark revenue for the farm. The final calculated revenue for the farm is the actual county yield for a given year times the final MYA price for the year. If the final calculated revenue is lower than 86 percent of the benchmark revenue for the year there would be an ARC-CO payment for that year. There is also an “ARC-IC” farm program choice, which is based on farm-level yields; however, in many instances the ARC-IC program has less payment potential than the ARC-CO program. Many times understanding the formula for the ARC-CO programs can be a bit confusing. Sometimes it can be easier to understand by reviewing the data and results for the ARC-CO program from previous years. For information on current and past benchmark yields, prices and revenues, historical ARC-CO payment levels, and other farm program information, producers should access the USDA ARC-PLC web site, which is at: www.fsa.usda.gov/arc-plc The 2023 corn and soybean yields in many portions of the Midwest ended up better than expected, considering the very dry weather that existed in many areas during much of the growing season. In the areas that had final 2023 county average yields that were near or above the established 2023 county benchmark yield for the county, there will likely be very little chance of receiving any 2023 ARC-CO payment this Fall. However, in portions of the region that had final county yields that were well below average, there could be some possibility for a small ARC-CO payment. The 2023 county yield data for all crops in every State is available on the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) web site at: http://www.nass.usda.gov/. The market year average (MYA) price for corn and soybeans is 12-month national average price in a given year from September 1st during the year of harvest until August 31st the following year, which is then finalized on September 30th in the year following the production year for the crops. This is why any farm program payments that are earned for a given crop year are not paid by USDA until after October 1st in the following year. The marketing year to calculate MYA prices for wheat and other small grain crops is from June 1st in the year of harvest until May 31st the following year. The 12-month national average MYA price for a given crop is based on the monthly average market price received by farm operators across the United States, which is then “weighted” at the end of the year, based on the volume of bushels sold in each month. The USDA MYA price estimates can be tracked on a monthly basis in the monthly USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) reports. The next WASDE report will be released on May 10. Following is a brief summary of potential 2023 farm program payments for each crop:

In summary, unless a producer was in a county that had greatly reduced yields in 2023 due to drought or other weather issues, it is unlikely that there will be any 2023 ARC-CO payments earned for corn, soybeans or wheat for the 2023 crop year. In addition, there will not be any 2023 PLC payments for any of the three crops. It may be possible that there will be either PLC or ARC-CO payments for other farm program eligible crops. Looking ahead to the 2024 crop year, there could be more potential for farm program payments for corn and soybeans. The 2024 reference prices for potential PLC payments in 2024 increased to $4.01 per bushel for corn and $9.26 per bushel for soybeans. The 2024 benchmark prices for ARC-CO payments increased to $4.85 per bushel for corn and $11.12 per bushel for soybeans. If current price trends continue past the 2014 harvest season into to 2025, there will be an increased likelihood for corn and soybean ARC-CO payments, especially in any counties that have reduced crop yields in 2024. The wheat reference price for 2024 remained at $5.50 per bushel and the 2024 reference price increased to $6.21 per bushel. Note - For additional information contact Kent Thiesse, Farm Management Analyst, Green Solutions Phone - (507) 381-7960; E-mail - [email protected] |

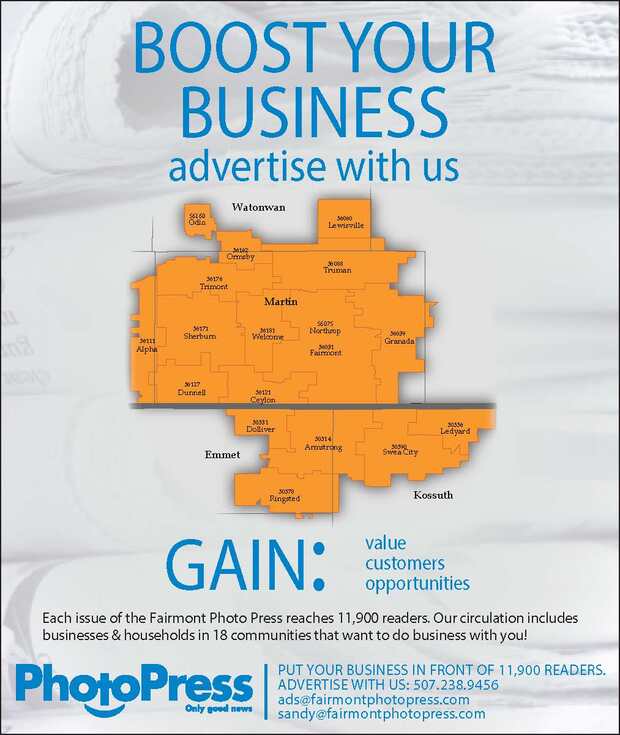

Contact Us:

Phone: 507.238.9456

e-mail: [email protected]

Photo Press | 112 E. First Street |

P.O. Box 973 | Fairmont, MN 56031

Office Hours:

Monday-Friday 8:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Phone: 507.238.9456

e-mail: [email protected]

Photo Press | 112 E. First Street |

P.O. Box 973 | Fairmont, MN 56031

Office Hours:

Monday-Friday 8:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m.

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed